Sometimes history’s most pivotal moments begin with the simplest of conversations. On an ordinary evening in Silver Spring, Maryland, three distinguished scientists gathered for dinner at the home of James and Abigail Van Allen, unaware that their casual discussion would ultimately reshape international relations and scientific cooperation on a global scale.

The conversation that would change everything started when Lloyd Berkner, a decorated naval officer and brilliant radio engineer, posed a seemingly innocent question to his colleague Sydney Chapman, the renowned British geophysicist: “Sydney, don’t you think that it is about time for another international polar year?”

This casual dinner party inquiry would eventually lead to one of the most significant diplomatic achievements of the 20th century—the Antarctic Treaty. The three men seated around the Van Allen family table that evening were all luminaries in their respective fields, with Van Allen himself being a celebrated nuclear physicist whose contributions to space science would later be immortalized in the discovery of the Van Allen radiation belts.

Berkner’s question wasn’t made in isolation. The scientific community had long recognized the value of coordinated international research efforts, particularly in the polar regions where extreme conditions and remote locations made individual national efforts both costly and less effective. Previous International Polar Years had demonstrated the immense benefits of collaborative scientific endeavors, yielding breakthroughs that no single nation could achieve alone.

The timing of this dinner conversation proved fortuitous. The world was emerging from the devastation of World War II, and the Cold War tensions were beginning to crystallize between the United States and Soviet Union. Yet despite growing political divisions, the scientific community maintained a strong tradition of international cooperation that transcended national boundaries.

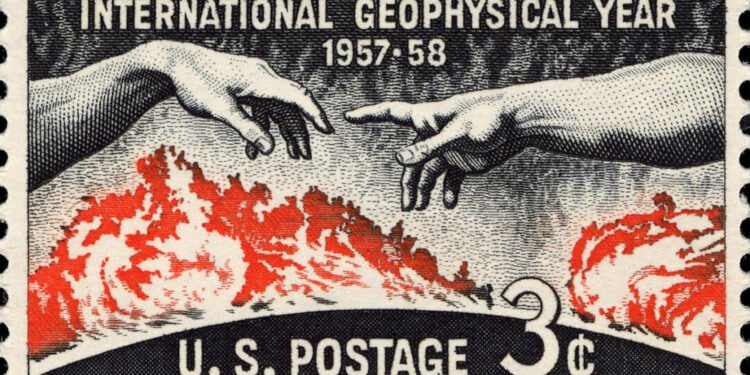

What made this particular evening so remarkable was how a simple question over dinner and brandy would evolve into a comprehensive framework for international scientific collaboration. The three scientists’ discussion that night planted the seeds for what would become the Third International Polar Year, later expanded and renamed the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957-1958.

The International Geophysical Year would prove to be a watershed moment in both scientific achievement and international diplomacy. Sixty-seven countries participated in this unprecedented global research effort, conducting coordinated studies of Earth’s geophysical phenomena. The program yielded remarkable scientific discoveries and technological advances, including the launch of the first artificial satellites, which marked the beginning of the Space Age.

Perhaps even more significantly, the spirit of international cooperation fostered during the IGY provided the foundation for addressing one of the most pressing geopolitical questions of the era: the future of Antarctica. As various nations pressed territorial claims on the continent, tensions mounted over potential militarization and resource exploitation of this pristine wilderness.

The success of international scientific cooperation in Antarctica during the IGY demonstrated that nations could work together effectively on the continent without compromising their research objectives or security interests. This practical experience of collaboration provided a model for something far more ambitious—a treaty that would preserve Antarctica exclusively for peaceful scientific purposes.

The Antarctic Treaty, signed in 1959 and entering into force in 1961, represented a diplomatic triumph that emerged directly from the scientific cooperation initiated by that dinner conversation. The treaty established Antarctica as a scientific preserve, banning military activities, nuclear testing, and nuclear waste disposal while promoting international scientific cooperation and freedom of scientific investigation.

What makes this story even more remarkable is how a casual conversation between colleagues, lubricated by good food and brandy, could generate such far-reaching consequences. The informal setting allowed these brilliant minds to think creatively about possibilities that might never have emerged in more formal academic or governmental contexts.

Today, the Antarctic Treaty stands as one of the most successful international agreements ever negotiated, with 54 nations now party to its provisions. The treaty has not only preserved Antarctica’s unique environment but has also provided a model for international cooperation that has influenced numerous other multilateral agreements.

The legacy of that evening in Silver Spring extends far beyond Antarctica itself. It demonstrates the power of informal scientific collaboration to address global challenges and shows how personal relationships between researchers can bridge political divides that seem insurmountable at the governmental level.

As we face contemporary global challenges that require international cooperation—from climate change to space exploration—the story of how dinner and brandy led to the Antarctic Treaty offers both inspiration and a practical example of how scientific collaboration can pave the way for diplomatic breakthroughs.

The 1958 three-cent stamp commemorating the International Geophysical Year serves as a small but enduring reminder of this remarkable achievement. More importantly, it symbolizes how the curiosity and collaborative spirit of scientists can sometimes accomplish what traditional diplomacy cannot—bringing nations together in pursuit of knowledge and peaceful cooperation.